In Jesus Christ, the Hero par excellence of history, man finds the Hero supremely worthy of being followed and supremely capable of making him heroic.

This is because although we are in the presence of a divine person, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, Jesus Christ has a complete human nature. Nothing human is missing in him. The absence of sin does not make his humanity defective because sin is the anti-human reality, expression of the corruption introduced into man by the misuse of freedom by the first human beings.

But Jesus Christ is not merely an integral man. The manhood of the God-Man is the perfect manhood,firstly because of the absence of sin and secondly because his entire existence was a ceaseless expression of all that is true, noble and sublimely beautiful in human nature. As Kierkegaard once wrote:

“’Never was deceit found on his lips‘ (1 Pet 2:22) but everything in him was truth. There was not the distance of a moment of a feeling, of an intention, between his love and the law’s demand for its fulfillment. He did not say „No“ as the one brother did; neither did he say „Yes“ as the other brother, for his good was to do his Father’s will. Thus he was one with the Father, one with every single demand of the law, so that fulfilling it was a need, his only life necessity. Love in him was pure action. There was not a moment, not a single one in his life, when love in him was merely the inactivity of feeling, which hunts for words while it lets time slip by, or a mood which is self-satisfying, dwelling on itself with no task to perform. No, his love was pure action. Even when he wept, this was not passing time, for Jerusalem did not know what was needed for preserving peace. If those sorrowing at Lazarus‘ grave did not know what was going to happen, he knew what he would do. His love was completely present in the least things as in the greatest; it did not gather its strength in single great moments as if the hours of everyday life were outside the requirements of the law. It was equally present at every moment, no greater when he breathed his last on the cross at Calvary than when he suffered himself to be born in the Bethlehem cattle shed.“ (Soren Kierkegaard, Works of Love)

Each and every virtue was expressed by him during his thirty or so years of human existence.His entire life was of pure, uninterrupted perfect humanity. However, this perfection of his human nature was not exempt from the normal natural weaknesses: tiredness, hunger, thirst, ability to feel the sting of rejection and suspicion and horror at the sight of evil. For as the Second Person of the Trinity he had decided to take upon himself these weaknesses of the flesh of man.He who “though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form he humbled himself…“ (Phil. 2: 6-7).

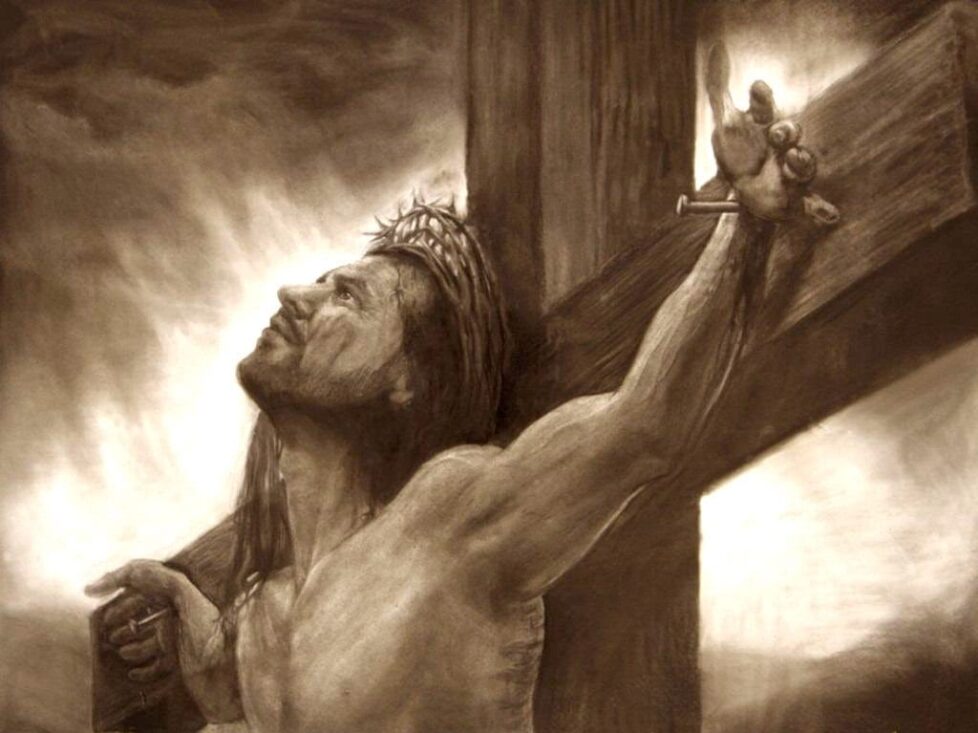

In this therefore lies not only a perfect human nature but a heroic human nature. This is because his lifelong heroism, from the crib to the cross, from dawn to dusk, during thirty years in Palestine, is the living out of what from the depths of eternity he had willed to do „for us men and for our salvation“.

His heroism culminated in the night of Gethsemane and the darkness of Calvary: in Jesus Christ Crucified we see and touch his heroism at its most dramatic and poignant. „And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross.” (Phil.2:6-8). As C.S.Lewis noted: “He [God] has paid us the intolerable compliment of loving us, in the deepest, most tragic, most inexorable sense.”

Hence the divine heroism is so sublime that all human heroism can but point towards it in wonder. Lewis wrote:

“He creates the universe, already foreseeing – or should we say “seeing” – there are no tenses in God – the buzzing cloud of flies about the cross, the flayed back pressed against the uneven stake, the nails driven through the mesial nerves, the repeated torture of back and arms as it is time after time, for breath’s sake, hitched up. If I may dare the biological image, God is a “host” who deliberately creates His own parasites; causes us to be that we may exploit and “take advantage of” Him. Herein is love. This is the diagram of Love Himself, the inventor of all loves.” (C. S. Lewis, The Four Loves)

In his heroic death Jesus Christ completed the archetypal role of the hero by confronting, fighting and vanquishing evil. But not any evil but the Evil par excellence, sin, and behind sin, Satan. To achieve this he, the Author of Life, descended into the kingdom of death, the land of darkness impenetrable to anyone except Him and destroyed sin and death, thus rescuing the human race from slavery to the satanic kingdom, as is portrayed in the icon of the Resurrection, the Anastasis, in which the mighty God-Hero pulls forth Adam and Eve from death.

Thus,in Jesus Christ lies the supreme instance of heroism and,since his humanity was masculine, it becomes the standard by which every man’s masculinity is measured.All human masculinity and heroism is a far-off echo of the supreme heroic act of the God-Man. The Incarnate God is history’s hero par excellence and all heroes are measured by the standard of his unique and sublime self-sacrifice, of the “no greater love” which led the Second Person of the Trinity to descend to earth and to shoulder the cross; the Hero, who, in order to liberate us, accepted “the punishment that brings us peace”, was “wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities” so that by his wounds we might be healed (Isaiah 53:5).

He is the Hero who can ask us for any sacrifice because of the sacrifices he took upon himself. What Alexander the Great said as he faced down the mutiny of the Macedonian soldiers in Ophis in 323 BC is an echo of what Jesus Christ says to every man following him:

“But does any man among you honestly feel that he has suffered more for me than I have suffered for him? Come now – if you are wounded, strip and show your wounds, and I will show mine. There is no part of my body but my back which has not a scar; not a weapon a man may grasp or fling the mark of which I do not carry upon me. I have sword-cuts from close fight; arrows have pierced me, missiles from catapults bruised my flesh; again and again I have been struck by stones or clubs – and all for your sakes: for your glory and gain.”