Sanctifying: Solving the World’s Greatest Problem

André Frossard, the French intellectual and convert to Catholicism, once asked John Paul II what he reckoned was the world’s greatest problem. The reply was swift and monosyllabic: “Sin”.

The World Wars with their millions of graves, orphans and widows, Dachau and Auschwitz; Communism with its “killing fields”; the “Culture War” of today with its millions of murdered babies in the womb and its looming threats to the old, the weak, the sick and the handicapped; horrendous is the sight of a world gripped by the fear of terrorist attacks; nauseating is the thought of millions of Africans and Asians undernourished on a planet with a surplus of food.

Yet all these scourges of mankind all ultimately began, developed and concluded in the human spirit where history is decided. They all point their bloodied hands towards their one master: Sin; for they are the many octopus-like tentacles of evil seeking to strangle mankind’s soul; the visible face of an invisible and far more devastating evil – the most real, the most terrible and the one with an eternal sequel. “The whole of man’s history has been the story of dour combat with the powers of evil, stretching, so our Lord tells us, from the very dawn of history until the last day.[1] The Enemy is at our frontiers, always has been and always will be until the world’s last night and the individual’s hour of death. It is the constant conspiracy, the age-old struggle against man, made up of the ancient triple enemy: “The Sleepless Malice”, the “enemy-occupied territory” of the World and the “Traitor Within” of our own terrorist- tendencies to what in itself is good: pleasure.

The effects of physical warfare are horrendous but eventually time heals or hides. Not so with the effects of spiritual war. In this life not only can you end up by living with the corpse of your own conscience as one of the “living dead” but there can be the boundless and unchanging consequences during endless ages for the secret defeats of this life. As the general Maximus, holding his sword in the air, said to the assembled army in The Gladiator: “Soldiers! What we do in life echoes in eternity!” So God has revealed to man and so the saints have lived. As St. Francis of Assisi prayed with great realism: “Praised be you, my Lord, through Sister Death, from whom no one living can escape. Woe to those who die in mortal sin!”

Sin is perennially present in history but never so dangerously as in our post-Western civilization. We now live in territory that is “enemy-occupied”, where the oxygen we breathe is the stifling air of the wastelands of the Enlightenment that rejected the oxygen of the supernatural. Within these lands the threat of global-warming to man’s body is taken ever so seriously but the danger of glacial-evil threatening man’s soul is denied or ignored.

The danger in time and for eternity cannot be over-estimated: “Finding himself in the midst of the battlefield”, asserts the Second Vatican Council, “ man has to struggle to do what is right, and it is at great cost to himself, and aided by God’s grace, that he succeeds in achieving his own inner integrity”.[2]

Therefore the only rescue possible for sin-stricken humanity lies in the salvation through sanctification brought by Jesus Christ. That is why the unforgoable burden of responsibility for this rescue operation lies primarily on the guardians of the sacraments instituted by Jesus Christ: the priests. To them in particular these words penned by C.S.Lewis apply:

“The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbour’s glory should be laid on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken. It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare.

„All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilisations–these are mortal,… But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit–immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.”[3]

Hence for the priest it is quite clear that “civilization” per se is not first on his list of priorities: well he knows where lies the “unum necessarium” – the individual soul in front of him in the confessional or at the baptistery.

We must be clear-minded that only grace can liberate man and society from the grip of sin’s corruption. It is time for us priests to adhere intellectually and practically to the truth of sanctifying grace abandoning any Enlightenment logic about “values” being enough to fix the world. “Take away the supernatural”, remarked Chesterton, “and all we are left with is the unnatural” -to this fact history is an eloquent witness, not least in the last century. Grace is not an optional extra if we are to perfect ourselves: only by grace will man overcome the consequences of original sin in his soul: a certain blindness of the intelligence, frailty of the will and terrorist-impulses from the passions.

Therefore to sanctify man through the power of the sacraments is to rescue him from the greatest threat in order to empower him to become a “new man” through participation in the divine life; to achieve the initial form of that utter fulfillment beyond man’s wildest imagination that God destines for him in Heaven. In this transformation the priest plays the vital role for it is he who procreates this new life by the powers given him through entry to the order of the priesthood; it is he who nourishes it , defends it , restores it, educates it when he stands at the altar, in the pulpit, at the baptistery, at the bedside of the dying Christian.

In doing this he lays the foundations for a Christian civilization for in empowering man to reach the “perfect manhood, that maturity which is proportioned to the completed growth of Christ” (Ephesians 4:13), he conquers spiritual senility in society at its source in the individual – and he unblocks the conduits of creativity in the individual minds of the specially gifted so that initiatives may overflow for the common good.

For the Church builds civilization by being first and foremost a school of sanctity training new men who will be the creators of a new world order. It is when the Church’s leaders, her priests, foster the secret activity of divine life in the depths of souls that the Church herself remains integrally loyal to her mission. Then the Church stuns the jaded world with astonishing outbursts of selfless dedication for the common good; with countless soaring initiatives in favor of man’s body and mind for in the graced heart of man there is a clarity of vision empowering him to see more and further; there is a power to love which endures.

For the engine of civilizational change is not the blind impersonal force of fate- there is no Hegelian “like-it-or not” juggernaut of progress. Nor is it ever per se the anonymous masses of people who change the world: it is individuals that matter. It is the individual with his intelligence and freedom who governs events and circumstances impressing on them his vision of reality. Within mankind some individuals through qualities of intelligence or will or social position or mere circumstances exert a determining influence on the building of civilization. As Christopher Dawson said “History is at once aristocratic and revolutionary. It allows the whole world situation to be suddenly transformed by the action of a single individual.” Accordingly culture is built up as the convergence and accumulation of such individual actions – and the history of Christian civilization is made by the cumulative force of countless individual decisions moved by grace.. Many a scepter’s decisions were conditioned by the lips that taught it’s holder his first prayers or gave him spiritual direction. How often has history changed its course because of a hidden prayer, a spiritual direction quietly imparted in the secrecy of a confessional, a Holy Communion, an anointing? Hidden indeed are the mysterious workings of sanctifying grace but powerful are the alterations to history.

Where would the Church be – where would the world be – were it not for the new men and women transformed by grace like Benedict, Leo the Great, Bernard, Francis, Dominic, Philip Neri, Teresa of Avila, John Bosco, King Louis IX and recent Roman pontiffs? From their supernatural life flowed a dynamism that radiated outwards to alter the structures of society.

As for instance in the case of one of the great statesmen in history, King Louis IX, who as king of France regularly stood for hours underneath the great oak tree in Vincennes to dispense justice to rich and poor alike. Yet his contemporaries knew why this ruler was different from so many others; they knew the secret sources of his wisdom, selflessness and justice for they saw him dedicating hours to prayer each day and they heard him admitting that for him the greatest treasure was not the throne but sanctifying grace.

Another changed man who changed society is St. Philip Neri, “an odd-looking fellow with bald head, bushy beard and tall ungainly body” ( Henri Daniel-Rops) who could be seen around 1590 in the streets of Rome. Yet this rather unlikely influence on civilization formed a motley group of individuals into what was called an Oratorio in the crypt of the little church of San Girolamo della Carità. From this unconventional group came movers and shakers of culture notably Baronio who is known to posterity as the great historian. Yet we can never forget that all the light,warmth and energy he gave to society began with the secret supernatural flame of a graced heart that revealed itself in his motto since teenage years “Live in God and die to self”, that spent hours of prayer amid the silence of the Catacombs of St. Sebastian and which was expressed on the streets of Rome with his charming invitation to all and sundry: “Ah, brother, is it today that we’re going to do good?”

Or St. Philip Neri’s contemporary St. Ignatius of Loyola – a quite different personality. Yet it was the adventurous Basque’s surrender to the supernatural through prayer and the sacraments after he had murmured to himself during his convalescence from war wounds, “If they became saints why can’t I?” that would burst forth in that extraordinary fountain of actual graces, the Spiritual Exercises. From it millions have drunk since the 1500s and their private victories have led to many public triumphs for Christian civilization: from the art of a painter known to the world as Michelangelo to the architecture of Bramante (who dropped everything each year to do his Ignatian Spiritual Exercises retreat), to countless rulers like President Garcia Moreno whose love of God led to the unprecedented progress of Ecuador, to the priests who created a new social order of breathtaking beauty among the Guaraní Indians of Paraguay.

Many of these unknown priests did not walk the corridors of power of the rich and famous. They walked other pathways leading souls out of the underground labyrinths of sin upwards to the sunlit lands of sanctifying grace where their souls bathed in light and warmth radiated Christian creativity. For ultimately that is the purpose of civilization: civilization is for man, not man for civilization and the purpose of man is to know, love and be united to God in time and for eternity. And for this the supernatural powers of grace are vital!

This supernatural dimension of the power of grace is not a dimension of history that will be accepted by the secular historian but it must be asked: is this not a limitation of his method? If the secular historian is closed in by the walls of rationalism how can he account for all those extraordinary individuals whom we Catholics call the saints with their unparalleled super-human selfless dedication to suffering humanity even unto death? How can he explain by mere natural or psychological causes thousands and thousands of selfless martyrs and virgins, men and women like John Bosco, Maximilian Kolbe or Teresa of Calcutta? A great modern historian, Christopher Dawson, author of a five-volume history of culture, recognized that any “theory of life” unable to explain these Christ-like individuals is inadequate.

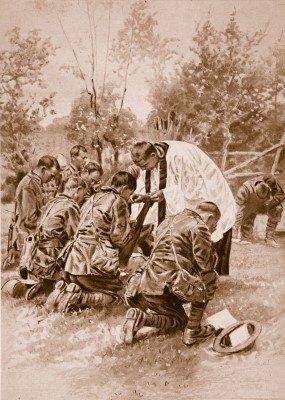

Hence we can never overestimate the importance of the sanctifying power of the quiet priest who built –and builds – true civilization: He baptized, blessed, gave the Bread of Life, healed the wounds of souls, brought joy on the day of the First Holy Communion; educated when no one else was educating; walked for hours on end to the bedside of the dying. Through spiritual direction and confession how many shipwrecked lives has he rescued? By anointing of the dying, how many souls has he led across the river of death to the eternal shores? Quietly he lived and quietly he died but when the circumstances of life called for heroism, the hidden heroism of heart he had been shyly guarding for years simply came to the surface. As in the case of Father Maturin, the Irish priest who was last seen standing on the deck of the Lusitania on May 7th, 1915, helping others to enter the last boats to leave the sinking ship.[4]

“Who welcomed your soul”, asked St. John Vianney “at the beginning of your life? The priest. Who feeds your soul and gives it strength for its journey? The priest. Who will prepare it to appear before God, bathing it one last time in the blood of Jesus Christ? The priest, always the priest. And if this soul should happen to die [as a result of sin], who will raise it up, who will restore its calm and peace?” “… After God, the priest is everything!”

Rising before the sun he kneels close to the flickering lamp at the tabernacle in order to bring about the unleashing of Heaven’s power in the souls of men through prayer; raising aloft the Sacred Host at the consecration, he performs the most sublime and single most important action man is in need of for through him the Eternal Sacrifice of Jesus Christ becomes really present here and now; he enables its power to stream through contemporary society touching hardened sinners, healing wounded converts, strengthening Christian warriors, mysteriously but really touching the hearts of non-Christians. All this happens because the priest is Alter Christus; Christ has identified him with himself as Head of his Mystical Body and the Father seeing him sees a mediator of the priesthood of His Beloved Son in whom He is well pleased and through whom he rescues the world from itself.

Among all of these priests are those whom the world rarely catches a glimpse of, hidden in remote monasteries and hidden hermitages in secluded valleys and on far-off mountain-tops. Here in the Alban hills to the south of Rome where I go hiking there is a monastery of Camaldolese hermits. On the large doorway there is an inscription: “Ecce Elongavi Fugiens et Mansi in Solitudine” (Psalm 54:8) (Fleeing I distanced myself [from the world] and remained in solitude). But of course the phrase hides the secret of why they fled from the world: it was for love of the world! Here these noble men pray for the world’s salvation– but their prayers are the prayers of the world’s greatest lovers who assault Heaven’s gates for God’s mercy upon the world; for the solution of the world’s greatest problem, the one that causes the greatest heartache and the only tragedy:sin – and for the utter fulfillment of man in unimaginable happiness in Heaven.

And all of this goes on undetected by the world’s radar. But not by Heaven’s – and neither by Hell’s.

Quietly and relentlessly, day after day, century after century, the effects of the priests actions show up in the secret depths of mens minds and at the hearths of families.

How many people have walked through life as happy men and women not knowing that their happy childhood was due to a priest who had quietly saved their parents marriage?

Who knows how many eccentric individuals have stayed within the limits of acceptable normality because of the power of the sacraments and the words of wise priests?

How many evils such as despair and the urge to suicide never reach the surface of society because of the hidden defenders of the city? For neither can we forget the subtle –but powerful – witness of the very presence of the priest especially through his sacred celibacy as a Nobel Prize winner in literature François Mauriac, remarked :

“Who is the priest for me…? It is always to one of them, whether living or dead, that my thoughts turn, when I begin to despair about man and the temptation to contempt clutches me. Deep down and without their being aware of it, the priests are the true poets, the only ones that have chosen the absolute, the only ones that have separated themselves from the world , much more than Rimbaud and all the idols of the youth of today, the only ones who have consented to receive that sign for eternity cutting down all the bridges behind them.[5]

Neither should we fail to recall the preventive role of the unknown priest’s activity in socio-political life. How many dictators, aspiring dictators, corrupt politicians, aspiring corrupt politicians, murderers, hate-filled individuals have been stopped in their tracks and had their lives changed because of the words of a quiet, unknown priest in the darkness of a confessional in an unknown parish? There will be some startling revelations about the connections between historical events at the Final Reckoning.

The world at times is certainly in a wretched state yet what would it be like if the guardians of the sacraments were not relentlessly sanctifying?

[1] Vatican Council II, Gaudium et Spes, 37.

[2] VATICAN COUNCIL II, Gaudium et Spes, 37.

[3] C.S.LEWIS, The Weight of Glory, pp.18-19.

[4] Father Maturin was the author of the insightful book on character formation, Self-Knowledge and Self-Discipline.

[5] LIEUTIER (ed.), Qu’attendez-vous du pretre, Plon, Paris, 1949 (my translation).