The Most Revered European in China’s History

Life magazine included this priest among its 100 most influential people of the second millennium and the Chinese communists included him with only a few other foreigners in the National Encyclopedia of China.

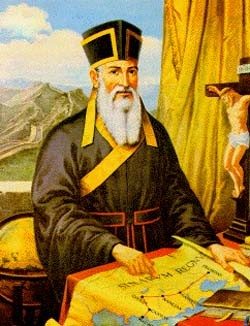

Father Matteo Ricci [pronounced Reetchee] (1552 – 1610), a “Son of the West,Brother of the East” is one of history’s greatest bridge-builders between civilizations. He was the only European to establish a deep and enduring intellectual relationship with the leaders of the ancient Chinese civilization because of his unprecedented knowledge of both cultures.

In doing so he helped bring about his deepest dream: to offer to the Chinese people the greatest treasure he possessed: the Catholic Faith. For Father Ricci -whose cause for canonization has already begun – was first and foremost a priest who longed to bring China to Christ.

That burning desire in his heart empowered him to endure twenty years drenched in failure as he sought to do what no Westerner had ever done before: penetrate into the heart of the Chinese intellectual elite.

Danger and death stalked his existence from the moment the twenty-six year old Italian seminarian of the Society of Jesus embarked on a galleon in Lisbon on March 24 1578 bound for India: pirates, epidemics and storms combined to give him only one chance out of two of arriving alive to his destination.

Indeed no sooner had he stepped ashore in India than he became sick with malaria; then on the journey between Goa and Macao in 1581 he became ill again and death seemed to be at his doorstep (in Shaozhou two of his brother Jesuits died of the disease). On his way to Beijing he suffered shipwreck on the Gan river and a Chinese helper died.

Fr. Ricci endured all of this along with suspicious eyes, arrests and imprisonment in the “Barbarian Castle”. No wonder he wrote: „we always have death in front of our eyes”. This epic struggle lasted for twenty years from 1581 until finally in 1601 he entered the Forbidden City by imperial decree of the Ming emperor as “ambassador of the West”.

There he received not only the emperor’s support and protection along with permission to live in Beijing but an admiration and respect for himself and the other priests hitherto not awarded to outsiders of Chinese civilization. The Emperor Wanli asked him to be advisor to the Imperial court due to the priest’s scientific and mathematical abilities for he predicted solar eclipses, introduced trigonometric instruments, and translated Euclid.

Thanks to the learning he brought to China shown in works such as his Map of the World ( six copies of which the emperor wanted in silk for his own palace), moral philosophy ( he wrote a treatise on friendship), the “Western master” broke through the Chinese prejudice about having nothing to learn from the barbarians outside of its frontiers. When he died in 1610 the emperor did what had never been done previously: he granted land for the burial of a foreigner.

Father Ricci’s greatest strengths were his deep Christian and priestly spirit, an attractive personality, a deep love for the Chinese people, great literary, scientific and philosophical knowledge and an eager willingness to learn everything possible about Chinese civilization to the degree that he became Chinese with the Chinese, “all things to all men” (1 Cor 9:22).

Fr. Matteo Ricci is an illustrious example of the priest as builder of civilization. Indeed his method – if it had been continued after him – might have led through centuries of patient teaching, conversation and effort to a Chinese Christian civilization, totally Christian, totally Chinese.

His achievement is also an incisive demonstration of the universal resonance of the Christian civilization built in Europe over a thousand year period for at the heart of its ethos was the quintessential Catholic vision of the harmony between the Catholic Faith and reason. Indeed one of the greatest influences in the method of Father Ricci was the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas since it is historically the most harmonious integration between rationality and divine revelation. As Fr. Ricci stated, he was convinced that the Chinese would accept „the things of our holy faith,” if these were „confirmed by much evidence of reason.”

Father Ricci’s penetration to the Forbidden City and the heart of Chinese intellectual leadership was never paid for in the coinage of hiding his Catholic, priestly and evangelizing identity.

His purpose was to intelligently and winsomely present the Catholic Faith as the one true religion to the Chinese people and he succeeded as attested by the conversions of such high-ranking Chinese officials as Xu Guangqi. Gradually and always with sensitivity he built up an “apologetic”, a philosophical dialogue between the perennial philosophical tradition of the Church and the Chinese philosophy of Confucianism.

It is important to notice however that he was severely critical of the Buddhist religion in China. In that sense Father Ricci followed in the footsteps of St. Justin Martyr and the other first Christian intellectuals who regarded philosophy and not religions per se as their partners in dialogue.

On the way he became known to the Chinese as Xitai, the „Occidental master”. Li-ma-teu (Ricci) is still building bridges between China and the West ( and more importantly with the Catholic Church) because of his enduring prestige. In 1983 China issued a stamp to celebrate the priest’s arrival in their country and other celebrations were held in his honor on the 400th anniversary of his death in 2010.

See SANDRO MAGISTER, A Ratzinger from Four Centuries Ago. In Beijing at https://chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it/articolo/1344985