At some moment in this drawing closer to Jesus Christ a man becomes aware that there is still a gateway through which he must pass in order to become a real comrade-in-arms: a willingness to be wounded in battle alongside the Hero.

This willingness to forget self, to die to self, to “lose” self, is the condition for passing from the stage of admirer to that of follower. If it does not occur, it means that the action of grace has been blocked and that prayer’s authenticity is suspect. It is the unbending law of spiritual growth,the gateway to becoming a true follower, and ultimately a comrade-in-arms of the heroic Christ.

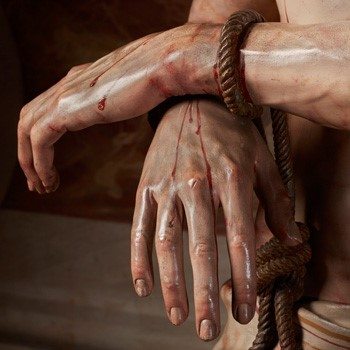

For the Supreme Hero had allowed himself to be wounded, indeed direly wounded. He had obeyed the iron laws in the world of Fallen Man: there can be no victory without pain, no triumph without loss, no love without sacrifice. The Supreme Hero did not exempt himself: he accepted the necessary pain and all the mess involved in becoming man.

“Our imitation of God in this life – that is, our willed imitation as distinct from any of the likenesses which He has impressed upon our natures or states – must be an imitation of God incarnate: our model is the Jesus, not only of Calvary, but of the workshop, the roads, the crowds, the clamorous demands and surly oppositions, the lack of all peace and privacy, the interruptions. For this, so strangely unlike anything we can attribute to the Divine life in itself is apparently not only like, but is, the Divine life operating under human conditions.” C. S. Lewis, The Four Loves, Intro., para.12, p. 17.

The Lord Jesus, however, transformed this pain into redemptive pain through the crucible of the self-conquest of his human will in an effort culminating in Gethsemane. He liberated us through the bloody sweat of that night and the blood-drenched body of Calvary. He liberated us by being a victim. Not by being a teacher or writer or leader but by being a victim. Thus Jesus Christ is Priest because he was Victim.

Therefore, we, who have been, or will be, identified with Jesus Christ by the seal of priestly ordination, know that suffering cannot be absent; sacrifice and self-discipline can never be strangers; self-offering in pain must always be possible. Yes, there will be pain; there will always be pain where there is true love: we will always be called upon to ride underneath the white and red flag. All priests – even if to a far lesser degree – repeat the experience of St. Maximilian Kolbe on accepting their priestly vocation:

“Then she [the Blessed Virgin Mary] came to me holding two crowns, one white, and the other red. She asked if I were willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both”. (Saint Maximilian Kolbe)

The truth is also brought home in the four main heroes of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. For the heroism of Aragorn, Gandalf, Frodo, and Sam has a certain priestly symbolism: they are willing to lose their lives for the sake of truth, justice and love according to the archetypal pattern in the life, death and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. Each makes a heroic decision, each undergoes a “passion” and each “resurrects”. Gandalf “dies” defending the Fellowship on the bridge of Khazad-dum but returns again as Gandalf the White. When Aragorn at the Council of Gondor decides to march on the Black Gate he was aware that:

“We must walk open-eyed into that trap, with courage, but small hope for ourselves. For, my lords, it may well prove that we ourselves shall perish utterly in a black battle far from the living lands; so that even if Barad-dur be thrown down, we shall not live to see a new age. But this, I deem, is our duty.” J.R.R.TOLKIEN, The Lord of the Rings, London, 1995, p.862.

Or in the case of the loyal Sam:

“But the bitter truth came home to him at last: at best their provision would take then to their goal; and when the task was done, there they would come to an end, alone, houseless, foodless in the midst of a terrible desert. There could be no return.

“‘So that was the job I felt I had to do when I started,’ thought Sam: ‘to help Mr. Frodo to the last step and then die with him? Well, if that is the job then I must do it. But I would dearly like to see Bywater again, and Rosie Cotton and her brothers, and the Gaffer and Marigold and all. I can’t think somehow that Gandalf would have sent Mr. Frodo on this errand, if there hadn’t a’ been any hope of his ever coming back at all. Things all went wrong when he went down in Moria. I wish he hadn’t. He would have done something.’

“But even as hope died in Sam, or seemed to die, it was turned to a new strength. Sam’s plain hobbit-face grew stern, almost grim, as the will hardened in him, and he felt through all his limbs a thrill, as if he was turning into some creature of stone and steel that neither despair nor weariness nor endless barren miles could subdue”. J.R.R.TOLKIEN, The Lord of the Rings, London, 1995, p.914-915.

Frodo accepts the vocation to destroy the ring even though it means leaving behind his beloved homeland, the Shire. This departure is a “dying” within Frodo and the “dying” occurs time and again as he journeys through Mordor to Mount Doom. The final “dying” before entry to his “resurrected” existence occurs as he departs Middle-Earth at The Grey Havens. As he explained to Sam:

“I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them so that others may keep them.”

It is love that is the secret force for this ability to die to self. In the case of Frodo, it was love for the Shire and Middle-Earth that kept the hero struggling as he travelled from the Shire to Bree to Rivendell to Mount Doom and finally to the Grey Havens.

But his pain brought redemption. At the end of the heroic epic, instead of a final clash of arms or a stirring speech we are shown the fruit of Frodo’s priestly sacrifice: the cottage of Samwise Gamgee, a haven of peace where Sam holds his child. The “priest” sacrificed so that others did not have to sacrifice.

And so do priests throughout the ages.Such renunciation of a great good like marriage or family always involves pain. However since it is pain for the sake of love, it fulfills man: all those who love enduringly know this: “not all tears are an evil” (Tolkien). And such love in the priest becomes redemptive, meritorious, and eternally enduring for others and for himself. Through the love-filled acceptance of pain we become co-redeemers with Christ of the world, true comrades-in-arms. As St. Paul said: “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church” (Col 1:24).

The Catholic, J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings, expressed the nature of the gateway of this strange transformation of pain into salvation and personal fulfillment as follows:

“Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament…… There you will find romance, glory, honor fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth, and more than that: Death: by the divine paradox, that which ends life, and demands the surrender of all, and yet by the taste (or foretaste) of which alone can what you seek in your earthly relationships (love, faithfulness, joy) be maintained, or take on that complexion of reality, of eternal endurance, which every man’s heart desires.” (TOLKIEN,The Return of The King p. 1006)

The French painter, Henri Matisse, who died in 1954 at the age of 86 expressed something of this truth during his final years when he continued painfully to paint placing a cloth between his fingers to keep the brush from slipping. One day someone asked him why he submitted to such pain. Matisse replied, “Pain passes, but beauty remains.”

Eternally.